- Home

- Cat Patrick

Tornado Brain Page 7

Tornado Brain Read online

Page 7

Emmy hit me in the face with the teltherbal at reces on purpos. Miss French didn’t beleeve me that it was on purpos but Emmy laffed about it with her frends and they all made fun of me for crying. She sent me to the nurse since my face is all red. Emmy is mean!

The reply from Tess on the same page said:

She’s mean! I’m sorry!

And under that, from Colette:

We beleive you Frankie I’m sorry your face hurts. I told Emmy I’m not going to her birthday party. She said she’s having chocolate cupcakes and I said I didn’t care because she was mean to my best freind. PS: Tess you’re my best freind too.

After a half hour of reading the same type of messages, I decided that there was no way the stuff we’d written in third and fourth grade would help Officer Rollins with anything other than knowing which kids were mean in elementary and that Tess was already starting to be a decent artist.

I got some water from the mini-fridge in my room before continuing with Fred. I knew what was coming: the page about our dare-or-scare game. Chugging my water, I thought back to when we made up the game. It was during winter break in fifth grade and we were bored.

“I’m bored,” I had complained to Colette and Tess.

“Me too,” Colette complained back.

“Me three,” Tess agreed.

We were on Colette’s covered front porch, wearing loads of layers, squashed three across in an oversize porch rocker meant for two. It was overcast and too windy to go to the beach.

“We could climb the roof,” Colette suggested. Her house is an A-frame; if you don’t know what that looks like, imagine a normal two-story house with a triangular roof, then chop off its lower level so the sides of the triangle nearly touch the ground. It looks crazy, like a house that sank into the dirt.

“We did that yesterday,” I said.

“I always slide back down,” Tess said.

“That’s because you don’t climb the right way,” I told my sister.

“Yes, she does,” Colette said, sticking up for Tess. “It was slippery.”

“We could do a quiz,” I suggested, knowing I was right about climbing.

“Okay,” Tess agreed.

“I’m over quizzes,” Colette said, which hurt my feelings a little since she knew I loved them. “Let’s put on my mom’s makeup!”

Tess’s eyes widened, and she sat up straight, smiling. Maybe it was because she was artistic, but she was really good at putting on makeup. She looked at me to see what I thought of the idea.

“No way!” I blurted out. “I can’t . . . ,” I began, tripping on my words. “The brushes . . . my face . . . it’s so . . .”

“It’s okay, Frankie,” Tess said, disappointed. “She doesn’t like the feeling of the makeup on her skin,” she told Colette.

“Oh,” Colette said.

I felt like I’d let them down, that now I needed to come up with something really great. I considered what the three of us liked to do together. All I could think was that we could make up a game. But not just any game: the best game!

“Let’s do truth-or-dare!” I said, jumping off the rocker because honestly I’d been too pinched in there for my liking. But I was on some medication that was keeping me from screaming about it, at least. Except it was the kind that made me feel shaky and hungry, so it still sucked.

I faced my friends. “We can make amazing dares!”

“I love that idea!” Tess said, beaming before her eyes clouded over. “Except we already know all of each other’s truths.” She bit her fingernail, thinking, then sat up straight with excitement. “How about dare-or-scare?”

Tess loves being scared or scaring people. You might think that’s surprising since she’s quiet and introverted and apologizes all the time and sometimes seems like she’s afraid of the world. But it’s a secret way Tess is really brave—braver than me.

“Um . . . ,” I began, not into the “scare” idea.

“What do you mean?” Colette asked. She looked intrigued.

“Well, you can either do the dare,” Tess said, “or you’ll get a scare!” She laughed wickedly.

“I don’t want to be scared,” I said, flapping my hands. “You know I hate that.”

“Then do all the dares.” Colette laughed. She put her pointer finger to her mouth, thinking, then said, “Maybe one of the dares will be to hug a tombstone!”

“No!” I said, my eyes wide, my heart racing.

“That would be better than waiting for someone to jump out at you,” Tess said. “And besides, you could do it in the daylight.” I must have looked terrified, because Tess added, “We can choose a prize for the person who does the most dares.”

“What kind of prize?” I asked.

“Taffy,” Tess said confidently. Taffy from Marsh’s was basically a food group.

“Good idea. Let’s start making a list of dares,” Colette said.

“Fine,” I said, not liking the possibility of visiting the graveyard but thinking that I was going to be the best at dares of all three of us. “I’m going to win and get all of your taffy.”

“No, you’re not,” Tess and Colette said in unison, laughing.

Tess checked the time on the phone she’d gotten for Christmas. “Frankie and I have to be home at five,” she said, frowning. “We need to do this fast.”

“Hold on,” Colette said, jumping up and running inside her house. She was back in seconds with Fred. “We can write the dares down in here.”

To my dismay, the first thing Colette wrote was: Hug a tombstone. She nudged me and smiled, telling me I’d be okay. From there, we all shouted ideas, Colette scribbling down the ones that all three of us agreed on: Climb Colette’s roof alone. Run your fastest from the inn to the water. Do jumping jacks in the middle of the arcade. And the list went on. We filled a whole page with dares, front and back. It took us so long to make the list that we didn’t get to do any dares that day—or, thankfully, scares—but we started the game the next.

Now, in my room, a smile I hadn’t even noticed building on my face melted away. Colette and I weren’t friends anymore. Tess and I didn’t have the same relationship either. They’d both betrayed me.

Sad, I picked up the photocopy of Fred and turned to the next page, looking forward to going back in time and reading our list of dares. But the next page wasn’t about dare-or-scare: it was another note about school. I flipped to the next, and it was doodles, mostly of tornadoes—by me, naturally. I turned all the rest of the pages that Officer Rollins had given me, completely confused. Either he hadn’t given me a complete copy of the notebook, or someone had torn out one of the pages.

All I knew was that there was no mention of the dares or scares in my copy of Fred at all.

chapter 8

Myth: You can outrun a tornado.

“CHARLES, I’M BORED,” I said, my chin resting on my hand, my elbow on the tall counter of the reception desk. Bored is my universal way of saying that I need something different to do, even if I’m not technically bored.

“Hmm,” Charles said, his eyes on the Rubik’s Cube in his hands. As he twisted the annoying puzzle over and around, I looked at the tattoos on his arms: the compass that was also a man’s eye whose hair morphed into the ocean with an orca breaching. There wasn’t any clear skin from his wrists to beyond his shirtsleeves. Way up on his shoulder, I knew he had a rose for his girlfriend before my mom, who died in a car accident. She’s the reason Charles gave up his corporate-lawyer job and moved out to Long Beach, so she’s the reason we know him at all, I guess. I was thinking about how much that probably hurt—the tattoos, I mean—when Charles said, “You could sweep the lobby.”

“No way,” I said.

“Bring in the cushions from the outdoor furniture? It smells like it’s going to rain.” The main door was propped open a

nd when I took my next breath, I realized Charles was right.

“There are always bugs on the cushions,” I said, shivering at the thought.

“Start a new pot of coffee?”

“You sound like Mom.”

Charles looked up at me and smiled, the skin around his eyes crinkling. “Maybe she’s right that I’m too soft on you and your sister.”

“If I do the coffee, is it okay if I go for a bike ride?” I asked.

He looked from me to some guests getting out of their car in the lot; he’d have to check them in soon. He sighed and set aside his Rubik’s Cube, then mussed up his own hair.

“I’m okay with fresh air in any capacity,” he began, “but today’s not a typical day, with Colette missing, and would you look at those clouds? It’s going to pour.”

“I like riding in the rain.”

He scratched his head. “Did you ask your mom?”

“I can’t find her,” I said. It wasn’t necessarily a lie, because I hadn’t seen my mom on my way from my room down the hall and down the stairs to the lobby. But I hadn’t looked for her either.

“I don’t know, Frankie,” Charles said, his eyes on the guests, who were loading up a luggage cart. “Do you have your phone with you?”

“Yes,” I said, nodding.

“Okay, then you can ride for a half hour,” he said, smiling at the guests as they came through the door. “Welcome,” he said to them. He looked at me sternly, like a kid pretending to be a grown-up. “Be back in exactly thirty minutes.”

“I will!” I called, not doing the coffee, waving behind me. With Charles engrossed in checking in the guests on the computer, I took one of the complimentary beach cruisers that people could use during their stay. He’d probably have said it was okay. Mom might not have. I had to take the green one because my favorite yellow one was still checked out.

I pedaled fast, picturing myself trying to outrun a tornado, looking back over my shoulder a few times on the way toward town, almost seeing it there behind me, just like the one in kindergarten. I imagined it crashing through the new fancy mini-golf course, sending golf balls flying; bulldozing the theater, making popcorn swirl into the air; and tossing aside the hut where you sign up for horseback rides on the beach.

A horn beeped at me when I paused too long in the middle of an intersection, mesmerized by my imagination. It made me jump and forced me to focus on what was real, the imaginary tornado sucked back into the sky. I quickly rode on, coasting down a few blocks, past the lots of land for sale and two motels. On Bolstad, I turned left toward the ocean.

The dare-or-scare game on my mind, I passed the parking spaces and the buoy, then took another left on the paved bike path that would take me back in the direction of the inn. I was riding in a huge circle. Heavy gray clouds loomed overhead, but no rain fell yet. There was so much going on in my head that I could have ridden all the way to Oregon but there was no way to do that and get back in half an hour.

What I wanted to know was why the dare-or-scare page was missing from Fred. I felt like it meant something. And I didn’t understand why or how Colette had had Fred in the first place: I felt like that meant something, too.

I pedaled fast and ducked quickly under the Decapitator, the part of the path that dips under the boardwalk. I passed the inn and kept on going. Houses were to my left, and grassy dunes with the ocean beyond them were to my right. I didn’t want to look left at a specific house for some reason. I didn’t dwell on it.

Pedaling, pedaling, pedaling, my mind spun. I’d ridden this path so many times, I probably could have closed my eyes and still known when the curves were coming. I was free to think, think, think of dares.

Do a headstand.

Bark like a dog in the middle of the cafeteria.

Ding-dong-ditch someone’s house.

Sing in public.

Stare at something gross for one minute.

Put on makeup without looking in the mirror.

Ask a total stranger for a french fry—and then eat it.

I felt like it was super-important to remember the dares we’d actually done. But no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t remember which we’d done, which had been rejected, and which I was coming up with right then and there. There were so many possible options: think of how many lines are on both sides of a piece of notebook paper!

“Ugh!” I shouted aloud. I hate my stupid memory! I shouted in my head, gripping the bike handlebars tight, wishing I knew why Colette had taken Fred, why the dare-or-scare page was missing, and why I was obsessed with remembering the challenges. Shouldn’t I have been more concerned about where Colette was than about a stupid notebook and game? I knew I should’ve, and yet I couldn’t stop myself from focusing on the wrong things.

Up ahead, there were two men sitting and smoking on one of the benches along the path. I didn’t want to get near them or ride through their smoke cloud, so I stopped the bike hard, skidding, and turned around. I was sweaty and out of breath from pedaling so fast.

The wind was picking up and riding wasn’t doing anything to organize my thoughts. I rode back without looking at one of the houses on the right. It made me feel uncomfortable. I didn’t dwell on it.

Nearing home, I saw Tess and Mom walking toward the cottage: it must have been dinnertime. Instead of taking the cruiser to the lobby, I left it against the side of the building, then went to meet up with them. I was starving.

* * *

—

ON FRIDAYS, MY family makes pizza and plays board games together. Tonight, though, Charles was still working at the front desk, and Tess refused to play anything. She and Mia had taken their cookies to Colette’s parents and Tess had been gloomy since she’d gotten back. I felt like there was something wrong with me because I still would have played a game despite maybe being worried about Colette. I don’t really know what worry feels like.

We watched a movie instead, something about a girl and a horse. Tess picked it. Mom texted a lot during the movie and got up once to take a call from Colette’s mom, which she took in her room with the door closed and which lasted for more than twenty minutes.

When she finally came back, her eyes looked red and puffy. “They still don’t know anything,” she said.

“Were you crying?” I asked.

“I’m okay,” Mom said.

“That’s not what I asked.”

“I know,” Mom said. “Should I make some popcorn?”

My mom’s popcorn is the best on the planet, so I said yes and forgot about asking her about crying. We unpaused the movie, and it started raining sideways, the drops tapping on the window like fingertips on a clicky laptop keyboard. I burrowed under a blanket and, with my eyes on the screen, watching the girl with the horse grow up to overcome her challenges, I daydreamed about growing up and becoming a meteorologist or chasing tornadoes or texting through a boring movie or being liked for being nice and funny instead of disliked for being weird.

I daydreamed about Colette knocking on the door to my room and asking for Fred, and me saying yes instead of no. About me asking why she wanted it instead of ignoring her and putting on my headphones. I daydreamed about Colette apologizing about February and inviting me to go do a dare with her—and me agreeing. I daydreamed about winning her taffy but sharing it with her, too.

I daydreamed about Colette being not-missing.

And then I ran through a downpour to bed, and I night-dreamed about her being okay, too.

PART 2

A Bad Saturday

chapter 9

Fact: Tornadoes are born from thunderstorms.

“HEYA, FRANKIE.”

“Hi, Teddy,” I said to the high schooler behind the counter at the arcade. He was helping someone else, so I had to wait.

Even though my stomach hurt, I was at the arcade right when

it opened at ten because going to the arcade was what I always did on Saturdays, and I needed to do what I always did instead of imagining Colette running away or being kidnapped or ripping out the dare-or-scare page from Fred and tearing it up to show me just how much we weren’t friends anymore. Except, as mad as I was at her, I couldn’t really picture Colette doing something like that.

It was a miracle my mom had let me come today with Colette missing and everything, but she’d been preoccupied by a guest who’d flooded his bathroom.

“Ready?” Teddy asked when it was my turn in line. I stepped forward, not looking at his face: his pimples made me cringe, but I concentrated on not commenting on them. Instead, I looked at the bulletin board on the wall behind Teddy. Colette’s school picture stared back at me from a MISSING CHILD poster.

Teddy looked over his shoulder. “Oh hey, that’s your friend, right?”

“No,” I said. “Can I get my card?”

“What’s the password?” he asked.

I rolled my eyes. “The password is ‘Give me my card.’” A pain stabbed my lower belly and I wondered if something I’d eaten was making me sick.

“Geez,” Teddy said, opening the register and retrieving my preloaded game card. Once a month, my mom put money on it and when it was out, it was out. I left it here so I wouldn’t lose it in my bedroom or on the way home or at school or anywhere else I went. Keeping track of things isn’t my superpower. “Here you go,” he said, handing it over. “Some kid puked by the new shooter, so I’d steer clear of that corner.”

“Thanks for the tip,” I said, taking the card and turning toward the side of the sprawling space farthest from barf corner.

There were a lot of people there already because Saturday was two-for-one day and people in Long Beach like a deal. I walked through bodies in the direction of my favorite starting point, Skee-Ball, with my chin awkwardly raised. I have to keep my chin up so that I can’t see the carpet in my lower field of vision. It’s black with blue swirls and red and yellow psychedelic stars intertwined among the swirls. It’s dizzying and is, hands down, the worst thing about the arcade. The flashing lights and noises never bother me, because they’re both expected—that’s what arcades look and sound like—and because they are constant. But I really hate the carpet.

The Originals

The Originals Forgotten

Forgotten Revived

Revived Tornado Brain

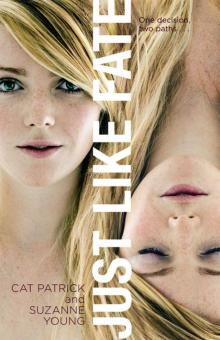

Tornado Brain Just Like Fate

Just Like Fate